Accessibility of the inaccessibility

For many of us, the only physical manifestation of the Internet in our home is the modem. Day after day the Wi-Fi signal, our passport to the Internet, can be plucked from the air as if it were nothing. All our files, photos and diary appointments can be stored just as easily in some cloud. We order our clothes online, look for love on the Internet and manage our finances through an app.

We do all this with little knowledge of where our files and data are being stored, who has access to them or who is looking over our shoulder at them. Nor do we have any idea of the immensity of the system served by the Internet.

Vision of evolution

The Internet is physical, no question of that.

It uses energy in gigantic quantities to supply our daily online needs. The lion’s share of this energy consumption is used for data centres. These constitute the heart of the Internet and of our digital existence. Here, servers are working 24/7 to keep the Internet “online”. It only requires a tiny staff to manage and monitor the enormous expanse of data floor. For all others, access to the centres is strictly forbidden.

Following up the foregoing

And now a new Tier IV data centre has arrived in the heart of Rotterdam. On a patch of as yet undeveloped land in the city centre.

It takes its place in the row of prominent buildings along the Coolsingel boulevard.

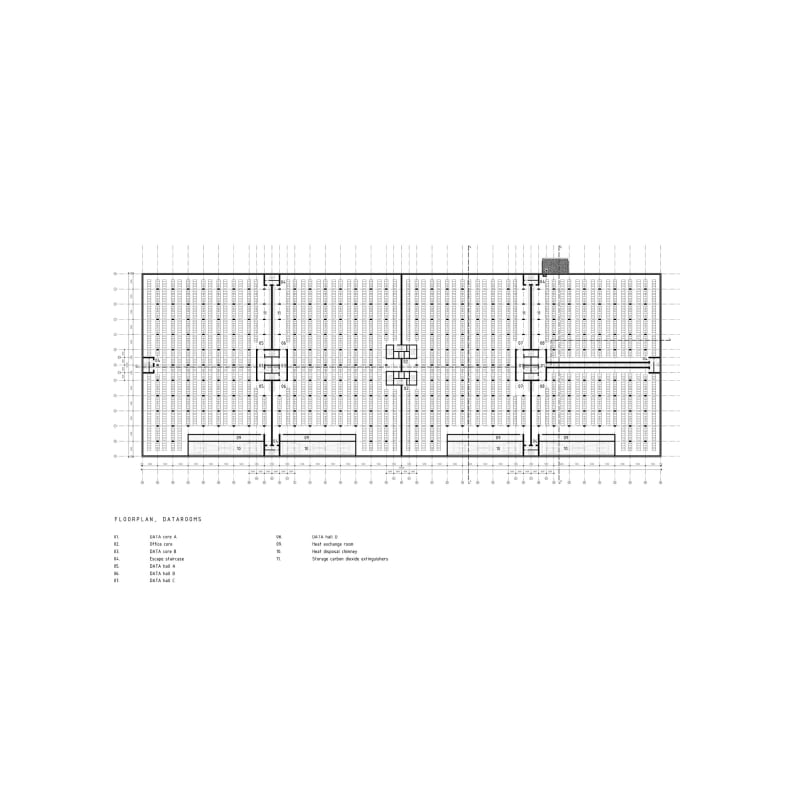

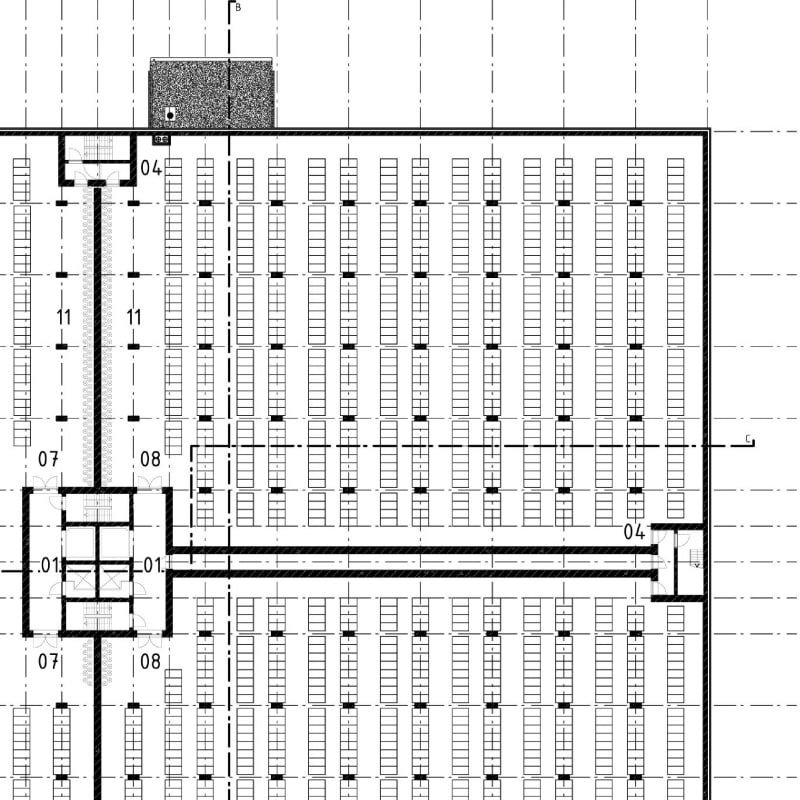

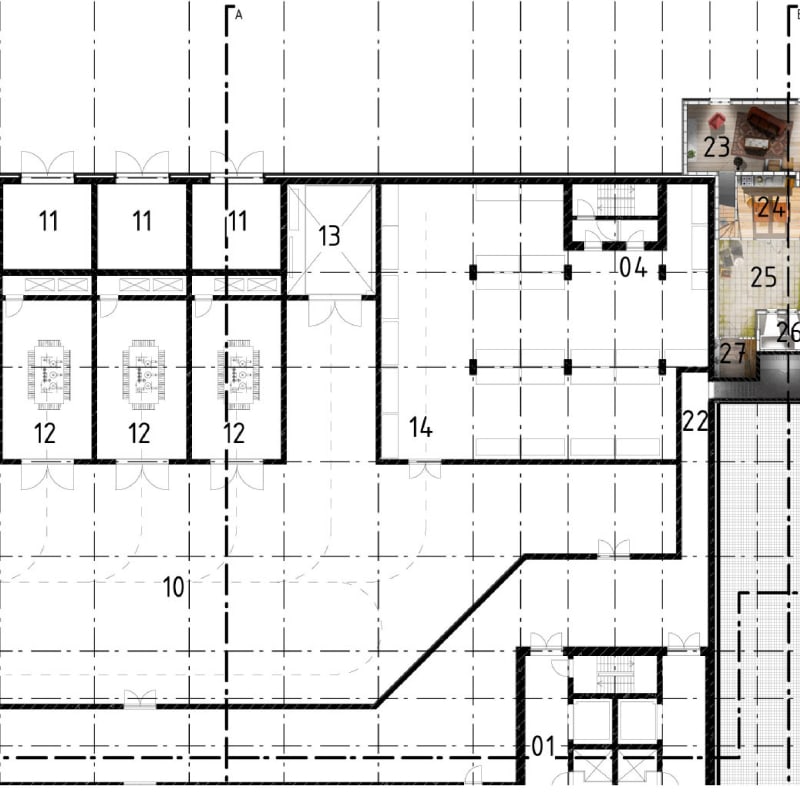

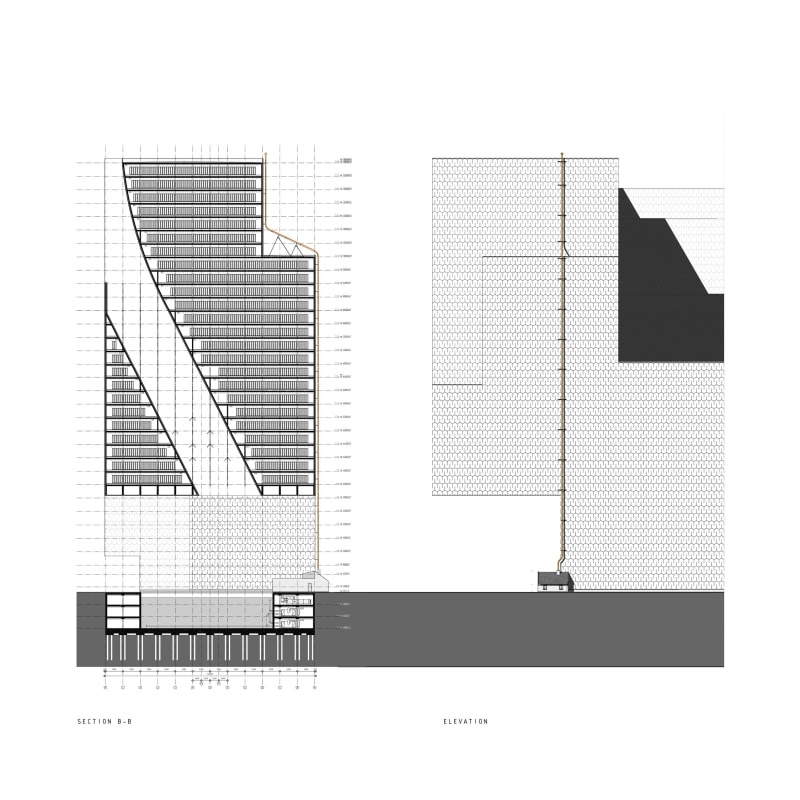

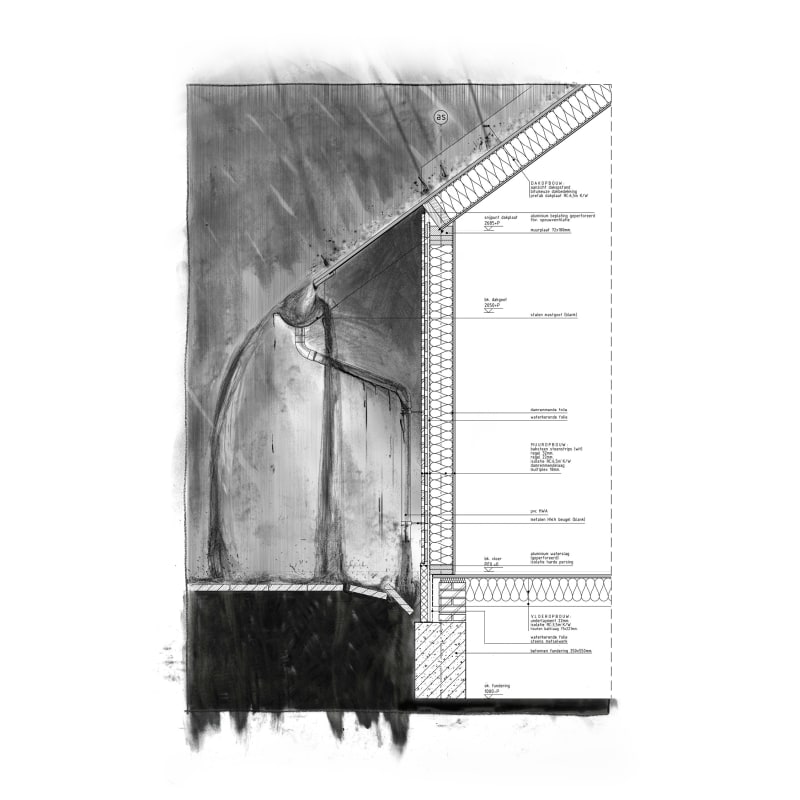

A block of 168 metres long, 65 metres wide and 130 metres high boasts 32 storeys with their rows of server racks.

Each storey is divided into four fire compartments, each no bigger than 2500 square metres. From every point in a compartment, a fire escape route is less than 30 metres away, all according to the dutch building regulations. In the event of fire, AR-N2-CO2, a deoxygenating gas, would be used to extinguish it. This rules out damage caused by fire extinguishing fluid and keeps the downtime of the data compartment to a minimum.

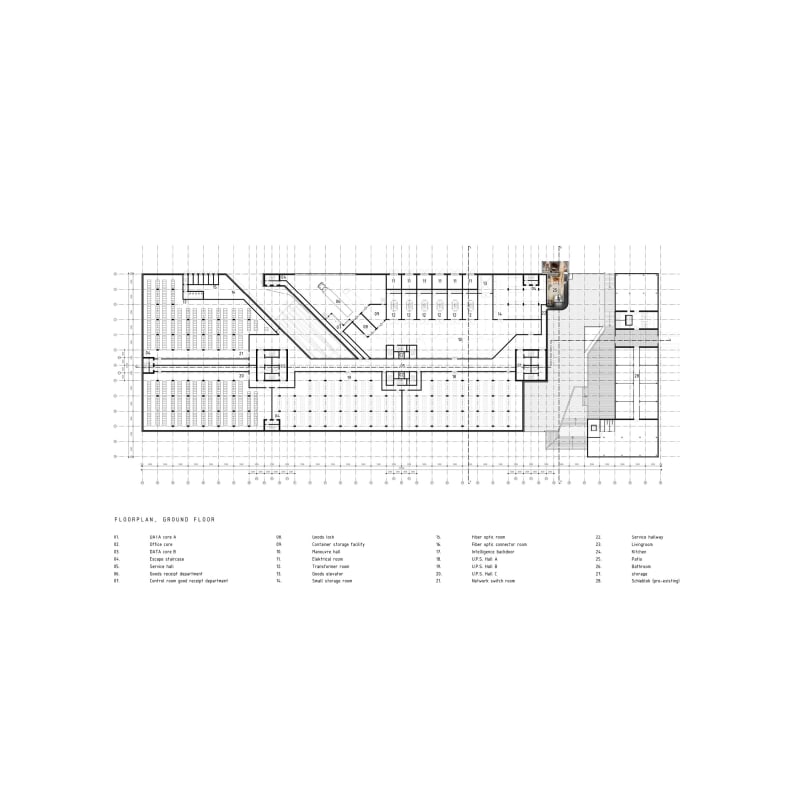

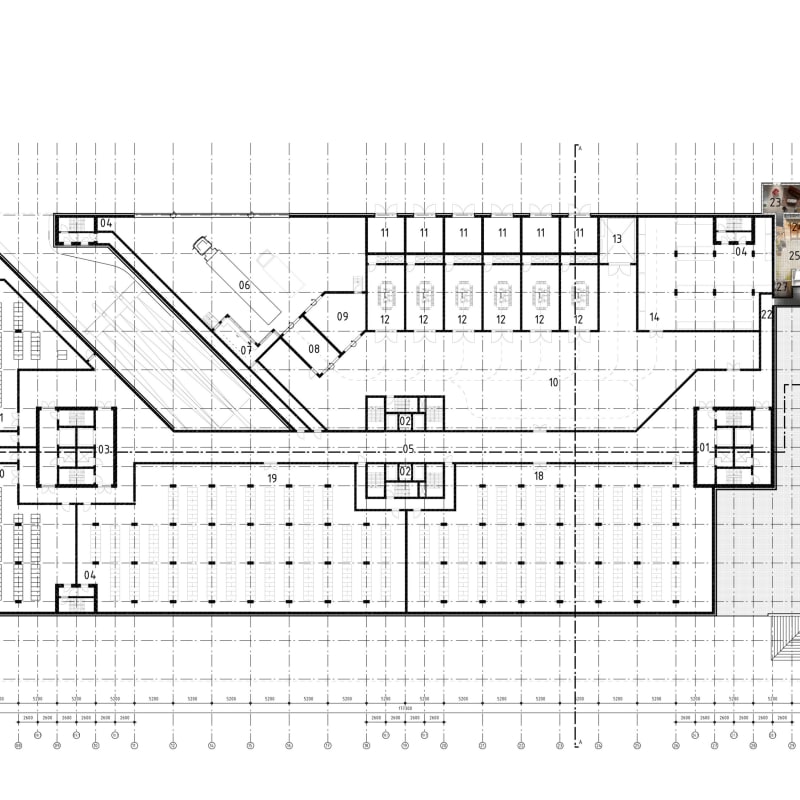

The fibre optic cable enters the building on the ground floor containing the dispatch bay, the transformer vault and the storerooms. In the event of a power cut, 14 diesel generators on the first floor take over the power supply.

The data centre has no entrance of its own.

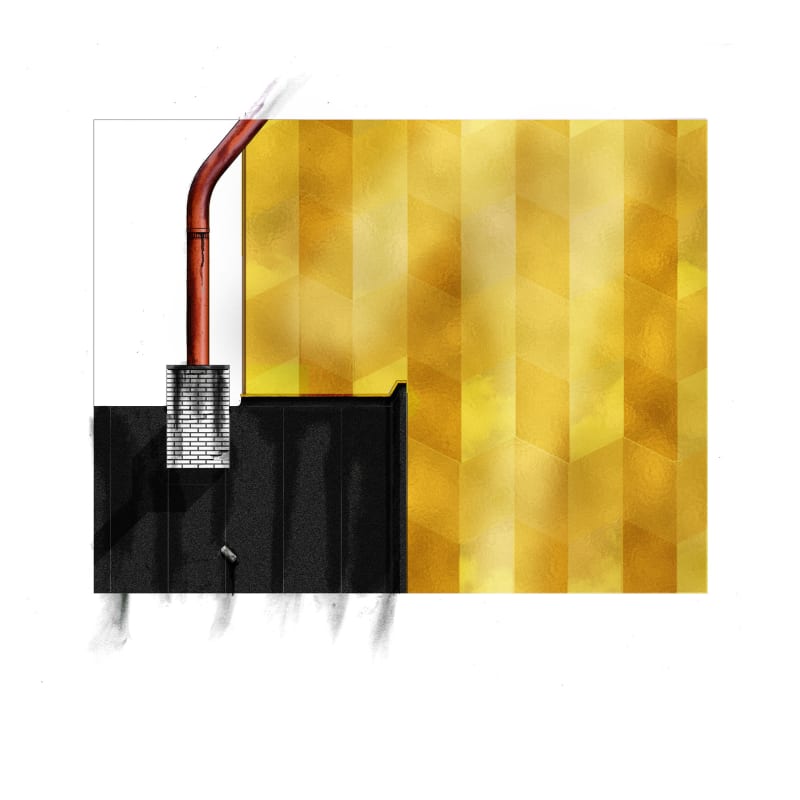

The aluminium frontage has a gold leaf cladding, which protects the building against unwanted signals, lightning and other weather conditions such as rain, snow and ice.

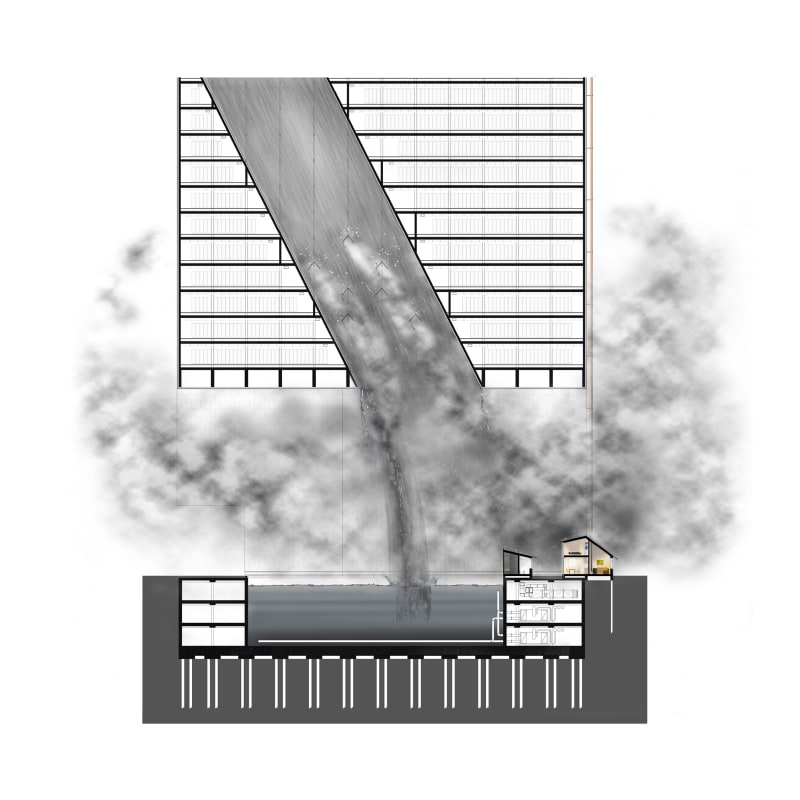

A shaft collects precipitation and conveys the water diagonally through the building to the reservoir below. Cooling ribs in the shaft and the rainwater collected in the reservoir ensure that the data centre is able to keep its interior cooled to the required 25 to 30 degrees Celsius.

In the shadow of your reflection

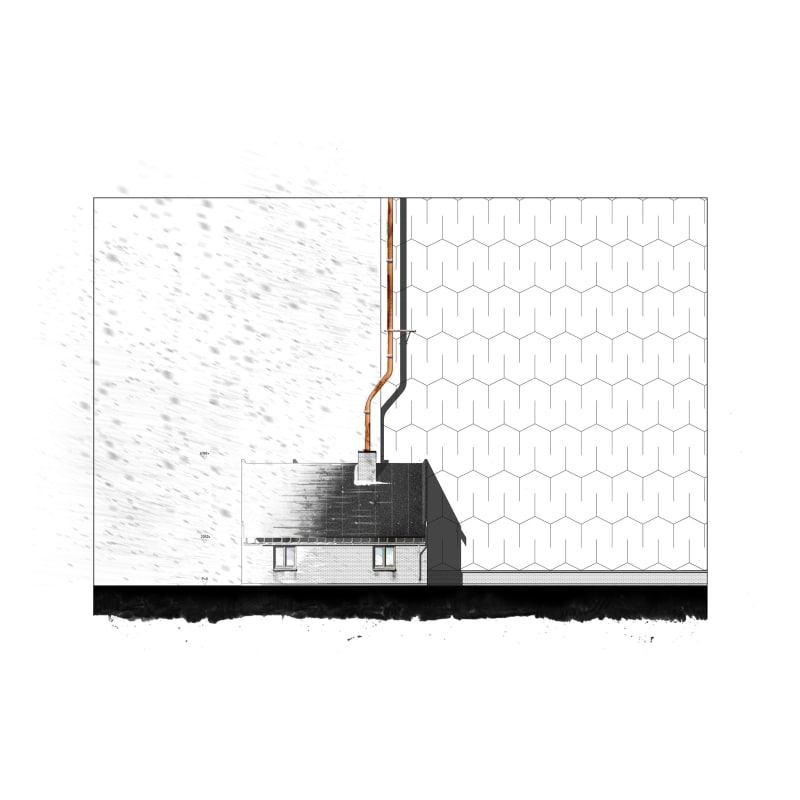

At the bottom of the shaft, on the shadow side of the data centre, a tiny house clings to the gigantic golden block. This is where the data centre’s caretaker lives.

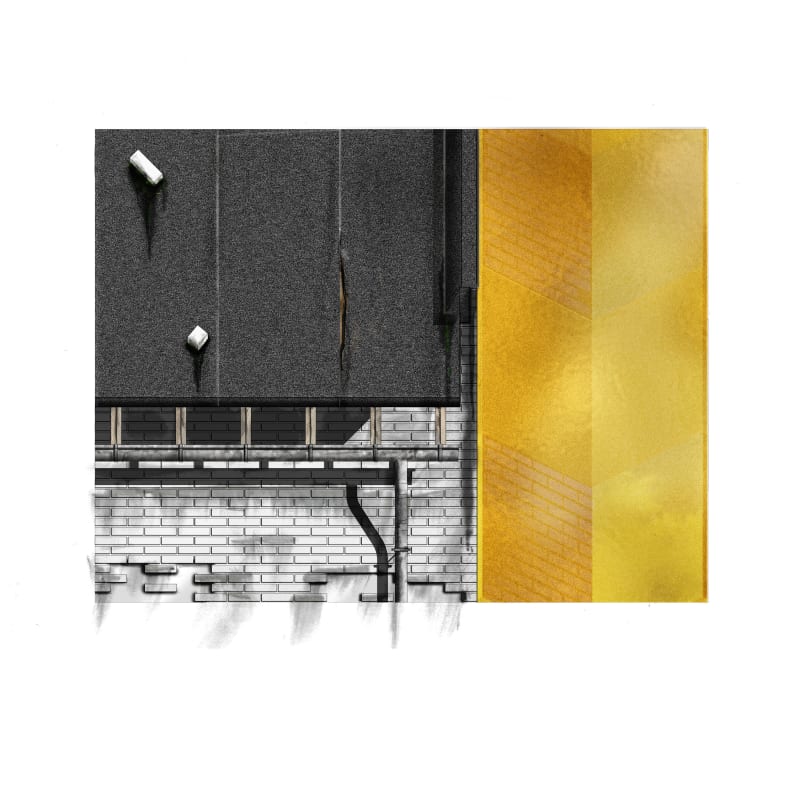

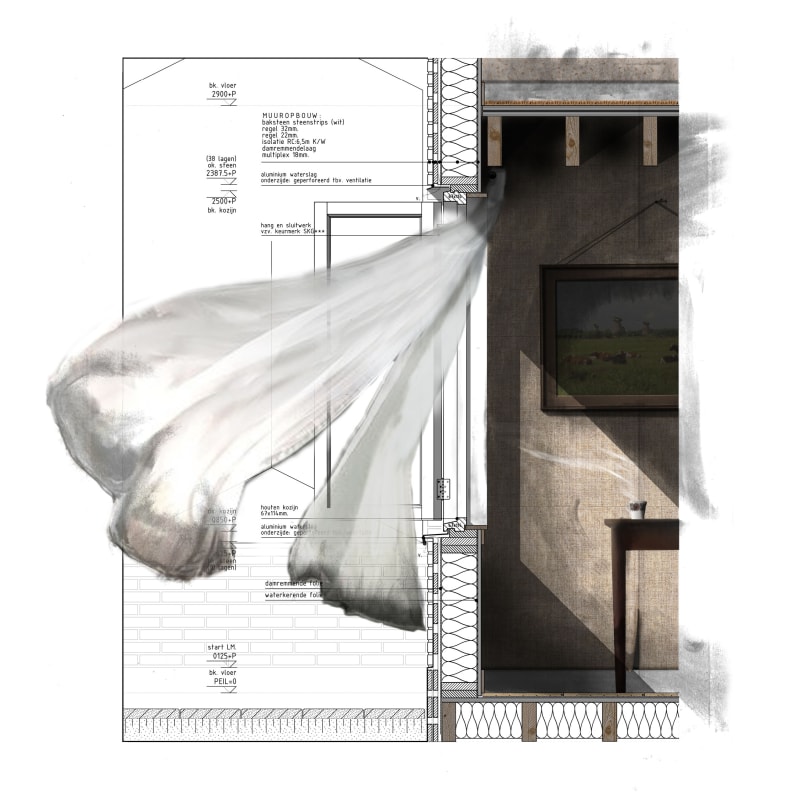

Unlike the data centre, the house’s aluminium sheeting is clad with white relief-free stone strips. The bitumen roofing conveys the water from the roof to the gutter; all window frames are clear varnished. The white timber front door has been reinforced with a steel inner side.

A secure corridor connects his house to the centre, so that he can intervene there in the event of a catastrophe. His live-in unit has every modern convenience. He has a bathroom of his own, a kitchen, a bedroom, a living room and a shed where he can store his tools and cans of paint.

A patio marks the centre of the house and can be accessed through the kitchen and the bathroom.

The living room boasts an old wood stove where the caretaker burns his briquettes until spring arrives.

A replica of the same

This morning the weather has brightened and the sky is a clear blue. The sun is visible through the shaft above the yard. Moss growing between the concrete paving stones in the yard is now bathed in a golden glow from the sun and its reflection in the data centre.

The white stone strips in the frontage have since dried but the rain has left grey streaks.

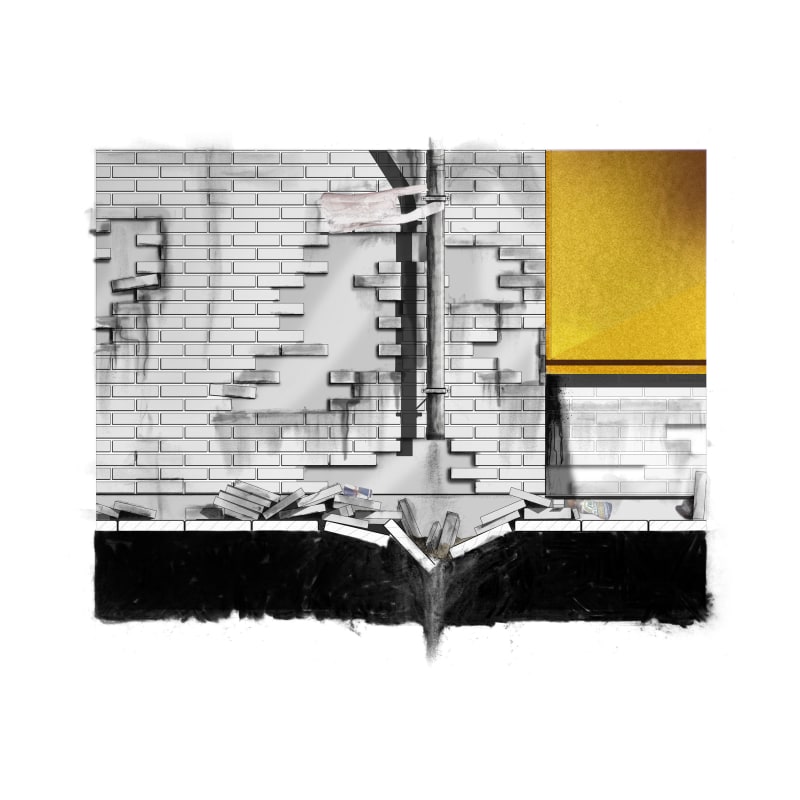

The caretaker opens the window and just then a stone strip falls from the outer wall to the ground, revealing the bare patch of aluminium sheeting behind. He stares at the stone but does nothing about it. It’s happened so often. His home is starting to show more and more bare patches. Increasingly, the white stone exterior is making way for matt aluminium sheeting.

The bitumen roofing is beginning to come away from the roof and bits of it flap in the wind.

The window frames look like they could do with a coat of paint and the strips of stone where the postman used to lean his bike vanished long ago. This is nothing compared to summer, when the sun and its heat cause the frontage to billow, leaving deep cracks in the jointing. Time, weather and use have all left their traces on the little house. After last night’s downpour the sun warms up the house again.

After last night’s downpour the sun warms up the house again.

The caretaker sat exhausted at the kitchen table next to the open window. He had been kept awake until the early hours by drips falling from the eaves into the metal gutter. Just once, he was on the point of getting up and stuffing a towel into the gutter to dampen the noise a little. But afraid of becoming too awake he remained lying on his back, waiting for the dawn.

A similar thing, a different day.

With the coffee maker now gurgling behind him, the caretaker stares out of the window at the fallen stone. He makes a mental list of what he has to do today in the data centre. It’s a fairly basic list for a place with so many secrets on board. It amazes him every time. “How can such a mighty machine be the cause of such meaningless tasks?”

As he drinks his first cup of coffee of the day, his attention is drawn to a wasp banging against the window in an attempt to find a way out. Slowly, he approaches the window with an empty glass and places it carefully over the wasp. With his other hand he gently slides a sheet of paper under it and brings it all to the kitchen table.

Taking a last gulp of coffee he looks at the glass.

The wasp is still looking for a way out with the little energy it has left. “Does it know it’s trapped in a glass? Does it even know what a glass is?”

The caretaker looks up from the glass and at the clock on the wall. Getting up from his chair with a sigh, he then makes his way through the dark, dank corridor. Enveloped in the smell of mould and decay he reaches the door at the other end. He puts his shoulder against the door and with his full weight pushes it open. The strip lights flash on automatically and he vanishes into the chilly glare of the data centre.